As we follow the travels of the latest Indian Revival, let’s look back at the history of Indian Revivals, with this reprint from 1968.

INDIAN! That magic name recalls the days when All‑American motorcycles, ridden by Red‑Blooded American men, accepted victory as their due at the Isle of Man TT, the GPs of Belgium and Argentina, the sands of Daytona Beach, and every board bowl and marbled flat track from Reading to El Centro. The distinctive bark of the flathead twin became part of the heartbeat of generations of American boys. There was no other Indian but the red Indian from the Wigwam at Springfield, Mass.,glowing redly, frame sharp black, smelling of heated metal and fuel, eager for the challenge of throughway or crooked lane. Indian!

If General George Armstrong Custer himself had been put in charge of the Indian works, the post‑World War II massacre of Indian hopes, plans, production, and racing victory could not have been more complete. The Indian tribe died 14 years ago. Yes, the name limped along with some Britishers masquerading in tawdry beads and trade blankets, but Indian, the Indian died.

Ordinarily, it would be safe to state flatly, “The Indian has gone to the Happy Hunting Ground.”

But has it? Those who decry the passing of the Great Red Motorcycle haven’t reckoned with the greatest Indian agent of ‘em all, Sam Pierce. In 43 years of riding, repairing, and haranguing at length on the real and fancied proclivities of Indian motorcycles, Sam, in profile view, has come to resemble the familiar hook‑nosed redman, emblem of Indian. With longer, darker hair, and some feathers entwined therein, Sam could stand as his own trademark signature illustration for the American Indian Motorcycle Co., his company, the outfit that has breathed new life into the once‑expired Indian.

Yes! Indian lives! Where Spanish Padres over a century ago built a mission for settlement of American aborigines, there now exists a neo‑Indian, an American Indian, built by Sam Pierce’s hands as a prototype machine, tribal leader for the American Indian Motorcycle Co. of San Gabriel, Calif.

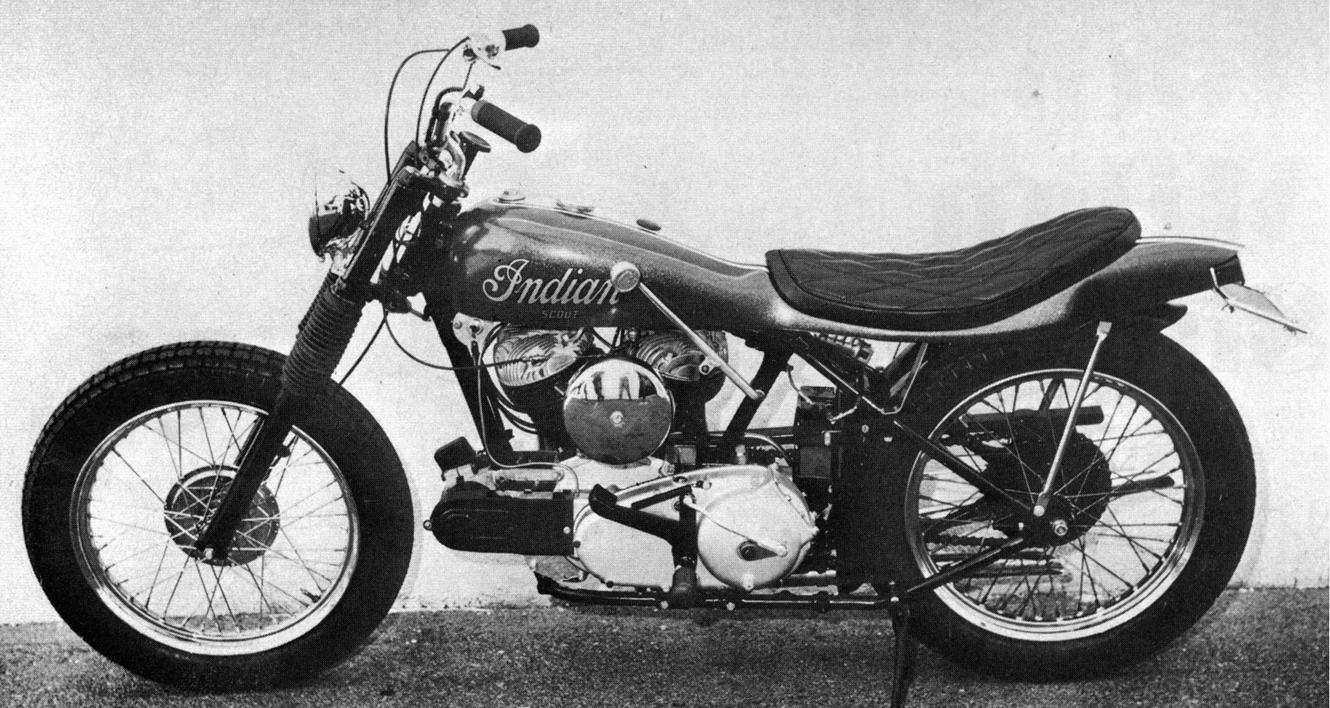

There it is, the Indian “Super Scout,” frame black as the inside of a mystic Kiva, tank red as warpaint ‑albeit metalflake red as a concession to modern times and this first of new Indians carries well the echoing names of its forbearers Prince, Chief, Warrior, Scout.

Indeed, the frame is Warrior, drawn from the vast stock of Indian motorcycle frames Sam Pierce has gathered from across the land over the years since ’53. Lithe as its namesake, fabricated of chrome‑moly steel in single toptube, single downtube configuration, the Super Scout frame carries Indian’s own telescopic, hydraulically damped fork forward, and rigid axle mounting at the rear. The fork is fitted with new seals and compound springs ‑ more modem practice ‑ but that rigid rear end is purely Indian. Sam plans to build rigid frame models for those who desire, plunger frame units for those who want them, and swinging arm Indians for the third group, though the latter may be custom fabricated.

“Forty‑five inches, forty‑five horsepower,” is how Sam describes his 45‑cu. in. flathead Indian engine ‑also built from stacks of cylinder barrels, a broom closet full of Timkin crankpins, drawers full of pistons, boxes of bearings, shelves of crankcase castings, and the hodgepodge of American standard thread nuts and bolts that make up the utterly indescribable ordered confusion that comprises Sam Pierce’s one Indian‑a‑day assembly plant.

Indian power need not be solely from 45‑cu. in. engines. For a thousand bucks, plus a few hundred or so more or less, Sam will recreate the Indian of his customer’s heart’s desire. The 30.50 (500 cc), or 600, 825 or 900 cc are available to the latter‑day Indian buyer. The engines are there, new or restored to mint condition, with freshly forged pistons and rods, glinting in the newness that abounded at the Wigwam 30 and 40 years ago.

Among the heads, liners, brakes, wheels, spokes, and tanks, is the collection of transmissions, some removed from defunct Indians, some discovered in a distant warehouse, embalmed in cosmoline, as if preserved especially against the day of resurrection in Pierce’s shop. The prototype Indian Super Scout is fitted with 4.02:1 Scout gearing, driven through the notoriously grabby‑when‑cold Indian assembly known to every schoolboy in the 1930s as the “suicide clutch.”

This left foot operated clutch, in conjunction to a left hand shift lever, complete with aluminum Indian head knob, comprises a gear change mechanism that is classic. Pierce, however, will locate the shift lever to customer taste, or, if present plans don’t go awry, fit more currently conventional left hand clutch, left foot change lever controls. However, Sam clearly regards this modification as something akin to leprosy, something unclean, un‑American, un‑Indian.

The red metalflake fuel/oil tank/seat combination is a molded fiberglass product of Don Jones and American Competition Frames. The sleek unit construction tank/ seat gives the newest of Indians a very healthy, competitive, contemporary appearance ‑ and contributes to the motorcycle’s lightweight, a mere 296 lb. without lighting equipment. Though Pierce minimizes the fact, in preference to redskin red, the tank/seat is available in any color.

Electricals are standard Autolite components ‑American as . . . as . . . as Indians. The chain driven generator for the prototype Scout 11 is clamped to the downtube, forward of the engine. However, if the buyer desires, this unit may‑be tucked neatly under the battery box and gear driven off the rear of the clutch housing. This simply is one more roll‑your‑own feature offered by Pierce’s American Indian Motorcycle Co.

Pierce has combed the U.S., from cliffdweller country to the land of the moundbuilders, for parts. He has bought out the stocks of numerous dealers who once sold and serviced the great red machines.

Why?

The answer to that question was laced with exquisite badmouth for the HarleyDavidson Motorcycle Co., its people, and the machines it produces, but when the answer did filter through, it was as clear as human conviction can be. Sam Pierce said: “I aim to build what I think is the best motorcycle ever.”

After that one concise statement, Sam said he believes his American Indian will appeal to the sport rider, the individual who desires a motorcycle that can be flipped end over end and continue on in the brush, or can cruise at 75 mph when called upon for a day’s tour of the turnpikes.

Folding footpegs and riser handlebars, alloy engine mounting plates of Sam’s own design, a hearty mixture of absolutely standard Indian parts, and “$25 per cu. in., with lights, and a guaranteed 100 mph” are part of the Super Scout of the 1960s.

“I’m setting up for 300 machines. I plan to build one a day ‑ and I figure to sell ‘em faster than I can build ‘em. And, I’ve got enough Indian parts to keep all the Indians in the world running for the next 2000 years.”

The old‑time motordrome rider, the flat tracker who showed numerous competitors the hind end of an Indian through a haze of dust and castor oil, exudes confidence that the American Indian Motorcycle, indeed, will live on for 2000 years and that he’ll be around to try for 3000.

The boast is brash. The boast is Sam Pierce. He will turn out 300 American Indian Motorcycles at $1000 per copy.

Even in the shadow of the full‑to‑bursting parts warehouse, the incubator of the new American Indian Super Scout, Sam Pierce, now 54 years of age, is forced into this admission: “I can’t go on forever.”