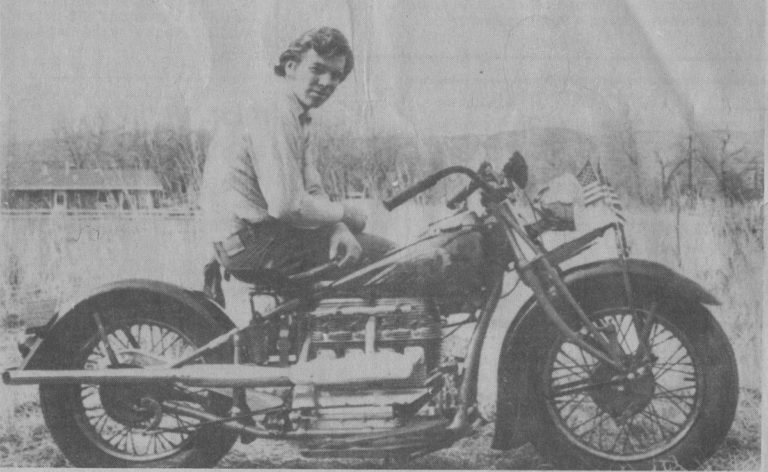

Inspirational Dottie Mattern rides a 1936 Indian Scout motorcycle 4,000 miles coast to coast in her seventies after surviving cancer.

Most people in their seventies are starting to slow down. Not Dottie Mattern. She’s still picking up steam. This fall the world traveler and seasoned rider trucked her beloved 1936 Indian Scout to Daytona Beach, Fla. She did it to embark on the adventure of a lifetime.

On Sept. 5, she and 102 other entrants from all over the world departed the famous beach town to begin a two-and-a-half-week sojourn to Tacoma, Wash., on antique motorcycles. She was one of only three females entered in the run that attracted regular Joes and rock stars alike, including Pat Simmons of Doobie Brothers fame.

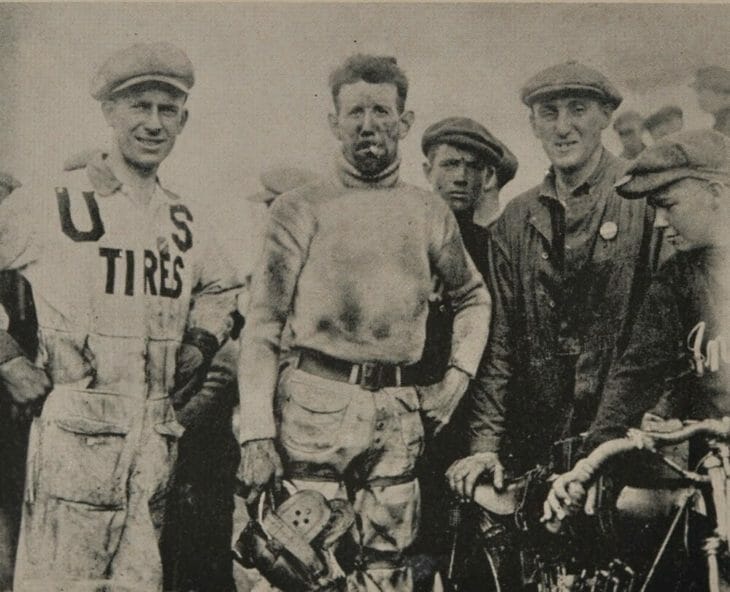

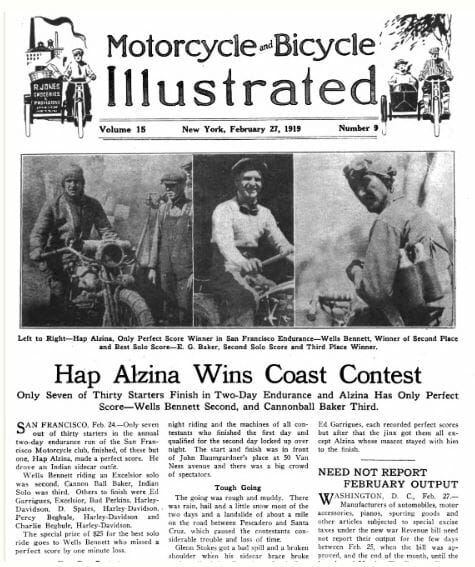

What prompted her to do it and what was the event that offered the challenge? The second half of that question answers the first: the challenge — which is something Dottie Mattern never shrinks from. The answer to the rest of the question is the Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Run, which is the brainchild of Lonnie Isam Jr. (Photo : Dottie Mattern Official Facebook Page)

(Photo : Dottie Mattern Official Facebook Page)

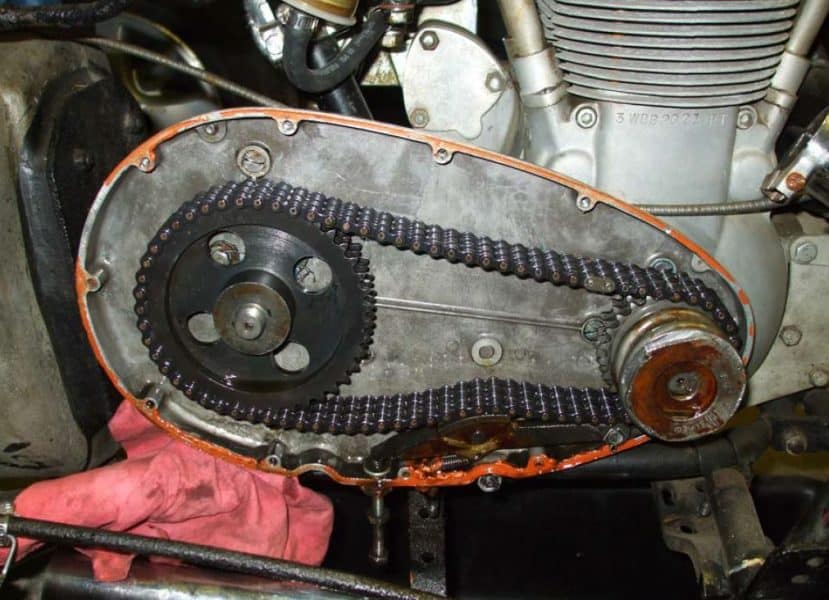

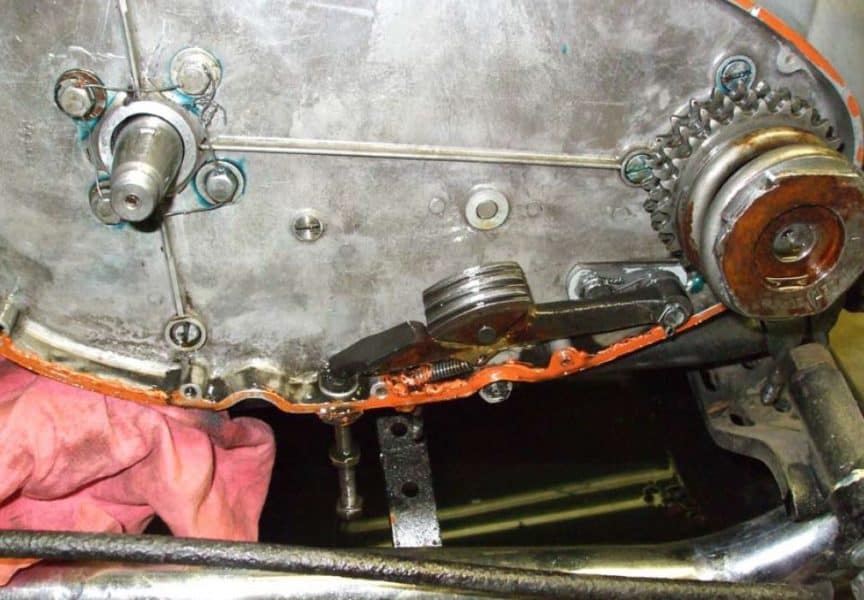

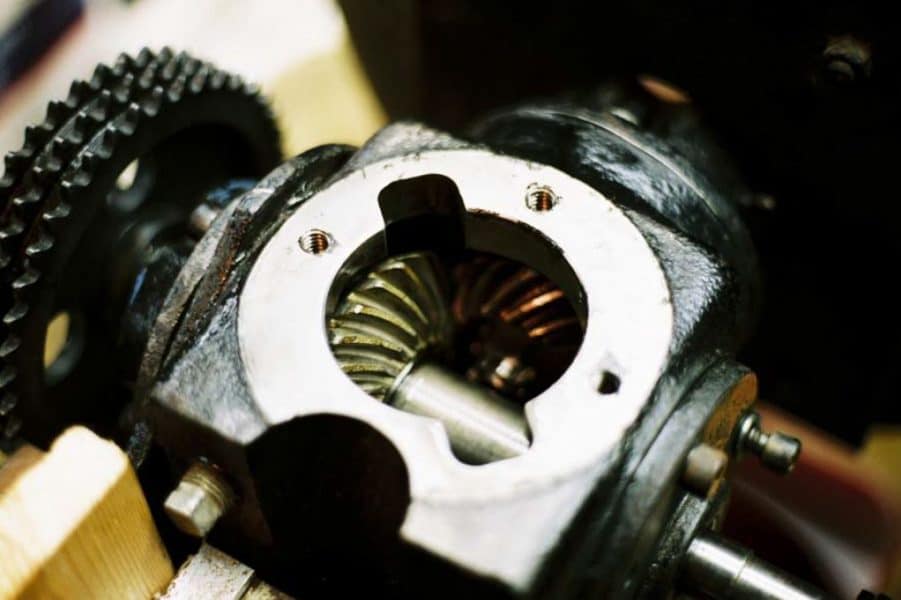

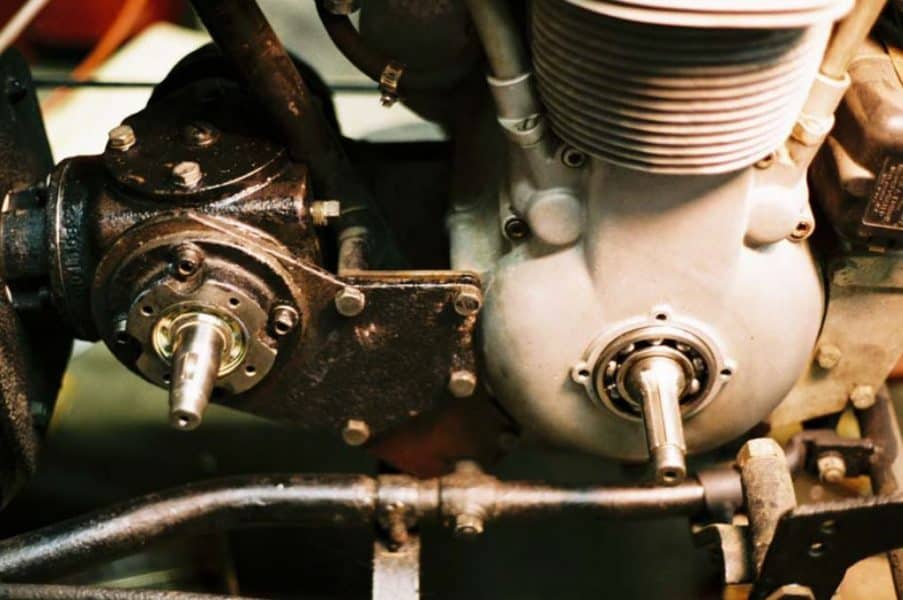

Dottie Mattern, Rider #43, rides her 1936 Indian Scout Motorcycle on the 2014 Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Run at the age of 70There have been three Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Runs since 2010. It’s held every other year in large part because it’s so difficult to coordinate, and most riders need the extra time to get their bikes together between events. The ride is as tough on the 80- to 100-year-old motorycles as it is on the riders.

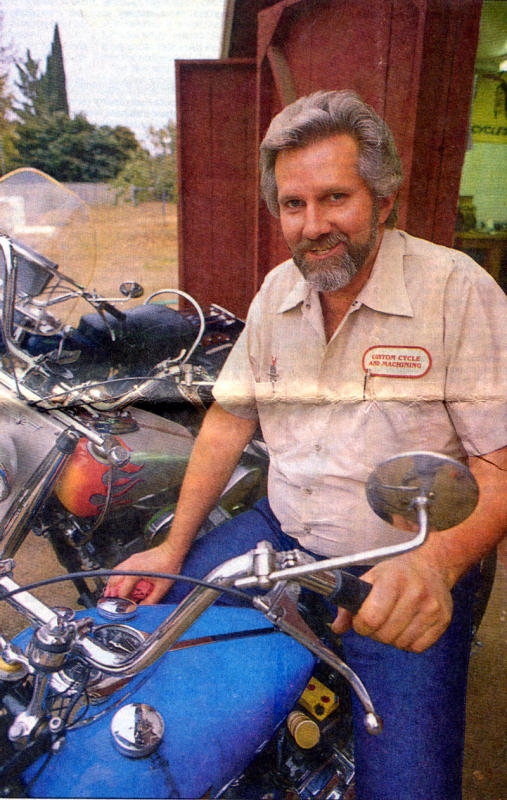

After hearing about the last two runs, Dottie Mattern was determined to enter herself. She began preparing the Scout in the winter of 2013. It was rebuilt from the ground up by Dennis Craig. Craig serves on The Antique Motorcycle Foundation with her.

Although she’s been riding since she was 19, and owned the Scout for 30 years, she didn’t really start to spread her wings until she retired in her 50s. She took up tennis at 50. She went to a week-long baseball fantasy camp where she was both the oldest and most valuable player at 54.

In 1999, at age 55, Dottie decided she wanted to become a ball “kid” for the U.S. Tennis Association. After a five-week tryout, she was accepted — along with roughly 100 children aged 12 and under. She did it for six years.

It was in September of 2001 that she’d be diagnosed with colon cancer. Like everything else in her life, she approached it with steely determination.

After beating it, Dottie became active in raising funds and awareness regarding testing. She hoped to raise $70,000 for the cause before, during and after her ride.

Her experience didn’t slow her down. Eight years ago she became a U.S. Tennis Official. In 2007, at age 63, Dottie Mattern set the East Coast Racing Association land speed record in Maxton, N.C., on a stripped down ’37 Indian Scout doing 74.1 mph.

Oh, and somewhere in between all this she found time to become a vice commander with the Coast Guard Auxillary. The moral to the story? Life can begin at any age, if you let it. Ride, Dottie, ride!

Source: Dottie Mattern, Seventy-Year-Old Cancer Survivor, Rides 1936 Indian Scout Coast to Coast On Challenging 2014 Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Run [EXCLUSIVE] : From A to B : Design & Trend