Jay Leno Explains the Indian 101 Scout Motorcycle

Starklite Cycle as shown on American Thunder. They interview Bob Stark about his dedication to keeping the Indian Motorcycle Brand alive for most of his life.

1912 Indian Single is a two-wheeler that Jay Leno just couldn’t pass up. In this episode he highlights the stock 1912 Indian Single and talks to its owner. The motorcycle was part of the Motorcycle Cannonball Ride and given its age, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to try it out. Yes, this 1912 Indian Single can still hit the streets. It’s owner Alex Trepanier tells us more about its history.

According to him, the 1912 Indian Single has been in their family since before he was born. His dad bought it for $650, back in 1962. Leno, of course, was pretty quick to offer twice the price. However, in this state, the 500cc bike has a current market value in the $70,000 range. Given the fact that it is unrestored and is still functional, the prize range makes sense.

When it comes to power, the 1912 Indian Single has a 4-horsepower single-speed. It has completed more than 3,000 miles in the Cannonball event. Also, it features a total-loss lubrication system. Thus, an interesting fact is that the engine probably consumed 5 quarts of oil each day.

Nevertheless, what Jay Leno is trying to point out is how much effort was put into making motorcycles in the early days. Not many could do it as Indian’s hand clutch and twist-grip throttle was pretty challenging. That’s why it took several false starts by Leno to make the vintage thumper run along. The 1912 Indian Single motorcycle’s top speed is around 35 mph.

But be that as it may, it surely is an exceptional experience to hop on this machine nowadays. The sound of the engine isn’t as pleasant as you would imagine but, all in all, it’s totally worth it. Check it out!

Source: 1912 Indian Single hits the street after a silly start up with Jay Leno!

Source: 1912 Indian Single hits the street after a silly start up with Jay Leno!

One of the oldest of the antique motorcycles that sat arrayed on Spanish Street on Tuesday afternoon was a 1916 Harley-Davidson, just a shade lighter than robin’s egg blue with a wide leather seat and broad, rounded handlebars.

Navy, red and gold pinstriping curled finely across the bicycle-looking frame, and the long, boxy gas tank bore the moniker “The Frankfurter.” Across the street, lounging in the shade on a bench outside the Brick Street Gallery antique store was the bike’s owner, Thomas Trapp.

He was one of more than 100 vintage-motorcycle enthusiasts rolling across the country in the motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Run. They started in Daytona, Florida, on Friday and made a pit stop in Cape Girardeau on their way to Tacoma, Washington.

Trapp runs a Harley Davidson dealership in Frankfurt, Germany, and says the run is the apex event for old-school gearheads such as himself. As he talked about the run, his blue eyes turned bright with the type of devotion to craft, bikes and lifestyle that motorcyclists are known for.

“Let me tell you,” he said in a round German accent, “I am riding vintage bikes for 40 years. I’m racing vintage for a long time. When you are into vintage stuff, I am always searching for the new thing, a new challenge.”

A 1916 Harley Davidson F owned by Thomas Trapp of Germany is displayed for the Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Run on Tuesday in Cape Girardeau.

A 1916 Harley Davidson F owned by Thomas Trapp of Germany is displayed for the Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Run on Tuesday in Cape Girardeau.

(Fred Lynch)He explained Erwin “Cannon Ball” Baker’s legacy is one of the most potent allures of the run. Baker set more than 140 driving records in his day, and his reputation for marathon rides is what inspired the event.

“He made it [across the country] in 12 days,” Trapp said, “in 1914 on an Indian [motorcycle].”

The motorcycles turn heads, to be sure, but some followers had traveled a distance to see the classic machines. Dave Sickmeyer has been following the competition online since it left Daytona. He and his wife Cindy came from Steelville, Illinois, to see them. He said the engineering of the Hendersons are his favorite part.

“How long have I been riding? Oh boy,” he said.

“His whole life,” Cindy assured.

Ron Roberts of New Hampshire rides his 1936 Indian Chief across the Bill Emerson Memorial Bridge for the Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Run on Tuesday in Cape Girardeau.

Ron Roberts of New Hampshire rides his 1936 Indian Chief across the Bill Emerson Memorial Bridge for the Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Run on Tuesday in Cape Girardeau.

(Fred Lynch)“Yeah, I’m 63; I’ve been riding since I was 12,” he said. He shifted his weight to ponder the midnight blue four-cylinder Henderson in front of him.

“Boy, I’d like to be able to buy an old bike like this, but you’re talking around 50 grand right off the bat.”

“What intrigues me is that they come from all over the world,” said Cindy. She said she was impressed by the German bike and at how old some of them were.

At 98 years old, Trapp’s bike isn’t much different from Baker’s original Indian, and the similarities don’t stop at the antique V-twin engine. The rules of the run allow for modification in the name of safety, Trapp explained, pointing at another driver rolling off his Henderson four-cylinder to fix a flat.

“See? He’s changed the wheelbase to get modern tires and a front brake from a BMW,” he said. “Which is totally fine for safety.”

But as he detailed his ride’s specs, a smile cracked across his sunburned face. He hadn’t installed a front brake. He hadn’t altered his wheelbase. What he’d done is position himself to compete in the run as a purist.

“There is nothing more in the world than the Cannonball on a Harley Davidson,” he said. “We are just about five or six people whose bikes are 1915 to 1919.”

When he brushed back his weather-beaten white-blonde hair, the inside of his right forearm bore an intricately inked rendering of a motorcycle: a 1916 Harley Davidson with a V-twin engine and a long, boxy gas tank.

“Yes, it’s the same one,” he nodded, beaming with pride.

Starklite Cycle as shown on American Thunder. They interview Bob Stark about his dedication to keeping the Indian Motorcycle Brand alive for most of his life.

Ever since Indian Motorcycle was revived by Polaris, the American motorcycle brand’s lineup of products has been growing fast. However, there’s one thing that all Indians have in common, from the entry-level Scout Sixty up to the luxurious Roadmaster Elite: they’re all cruisers. Since the brand is positioned to go toe-to-toe with another century-old name in American motorcycles, the new Indian Motorcycle has been competing exclusively in those segments, and it’s actually done a pretty nice job scraping out a market share for itself.

But for a while now, we’ve been hearing Indian promise that greater product diversity was on the way. Indian Motorcycle marketing and product director Reid Wilson told The Drive a year ago that the company would be “venturing into new categories with new models that push forward and expand Indian’s relevance with a wider range of riders.” A month later, Indian pulled the wraps off of the FTR1200 Custom concept bike, a motorcycle for the street that’s heavily influenced by the dominant FTR750 race bike that’s won that last two American Flat Track titles.

The concept was a hit and got a lot of attention, prompting Indian to confirm a production model in June and unveil the official FTR 1200 and FTR 1200 S production models this month. We went to the massive Intermot motorcycle show in Cologne, Germany where the bike was unveiled and had a chance to talk to a few big shots at Indian Motorcycle about how one of the most important American motorcycles in years went from a dominant flat tracker to a stunning concept to the first non-cruiser in Indian’s modern history.

One of those big shots was Wilson, the same guy who told us a year ago to expect a more diverse lineup from Indian. “You’d like to think it was a really clear and simple path, but we started working on this bike in March of 2016,” he said. “You make compromises and you figure out the best way to express [the spirit of the FTR750] in a way that is relevant for a street rider for something that will work on an everyday basis, but will still maintain the essence of the race bike.”

So it sounds like a production bike was the plan all along ever since Indian got back into flat track racing. It just so happens that Indian built a very good race bike and a concept that was extremely well-received, both of which aided in building hype around a bike that you’ll actually be able to buy.

Eric Brandt

Eric Brandt

Flat track champ Jared Mees aboard the FTR 1200 with some very enthusiastic Indian fans behind him.

Wilson went on to talk about how Indian surveyed the globe and spoke with thousands of riders about what they would want to see in a performance-oriented motorcycle from an American brand. Based on that feedback, the FTR1200 Custom concept was born. I asked Wilson about some of the challenges involved in turning the concept bike into a production bike.

“Exhaust is always challenging just due to the regulatory challenges we face. This is a global bike so we have to adhere to a wide array of countries’ standards,” he said, highlighting of one of the most noticeable differences between the concept and the production model. “The FTR1200 Custom is a very pure motorcycle, but it’s not a motorcycle you’d want to ride more than a couple hours at most. But you get on [the production bike] and you could ride this thing cross-country without a lot of compromises in terms of comfort. It’s quite friendly to the customer in terms of comfort and performance.”

Wilson went on to speak of the overall significance the FTR 1200 will hold in the American motorcycle industry. “The significance of this motorcycle is massive. I’m almost 40 and I grew up dreaming about this motorcycle from an American brand my entire life. To be able to work on it is a dream.”

Indian Motorcycle

2019 Indian FTR 1200 S

Next up was industrial designer Rich Christoph, the man who designed the FTR750, the FTR1200 Custom, and the FTR 1200 production bike. He detailed the importance of starting with a race bike and designing a street form around it.

“Thank God we went racing to begin with,” he said. “It would be really easy to just keep doing the same basic cruiser stuff and not get involved in flat track racing, but we challenged ourselves to raise the bar. We knew that racing would improve chassis development and powertrain development that got us information we can deliver back to the customers on our street bikes.”

“I was trying to capture the championship lines and the shape of the tank and carry those lines, silhouette, and proportions into the FTR1200 Custom. I had nobody in the way telling me what I could and couldn’t do. There were no restrictions. It was just pure sculpture, pure emotion, and pure mechanics.”

For anyone disappointed that the production FTR doesn’t look more like the concept, Christoph explained to me why they couldn’t just mass-produce the concept. “What I may have done is done it a little too well. Now you’ve gotta take that bike and dissect it. You need to cut a seat and real fuel volumes out of that silhouette. The 1200 Custom had high pipes on it and you’d burn your leg after about 20 km and at about 25 km you’d run out of gas. And it would be about $95,000 to build that and sell it on the street.”

Indian Motorcycle

Indian FTR1200 Custom

You hear that, naysayers? If you got a carbon-copy of the production bike in dealers like you wanted, it would almost have a six-digit price tag, not to mention its various practical disadvantages.

“All of those design challenges in making a real motorcycle at a cost that the customer is actually willing to pay for and fall in love with is a very delicate balance and it’s a big challenge,” said Christoph.

That design challenge was completely worth it, Indian’s international product director Ben Lindemann told me, expanding on the importance of the brand exploring segments outside of its bread-and-butter cruisers and diving into racing.

“As a brand, we were always known for racing,” said Lindeman. “When [Polaris] bought [Indian] in 2011 it was important to us from the beginning to get back into racing. Coupled with that, we wanted to grow outside of our traditional segments of cruiser, bagger, and touring bikes. We wanted to get into segments that are growing in the U.S. and are also really big internationally.”

“About four years ago we said ‘okay, let’s do a race bike and then let’s leverage that race bike to build a street bike.’ Once we did the race bike we got a lot of feedback and people loved how it looked so we knew we were on the right path.”

Indian Motorcycle- Jared Mees doing a burnout at the unveiling of the FTR 1200

Indian Motorcycle- Jared Mees doing a burnout at the unveiling of the FTR 1200

Indian Motorcycle

Indian Motorcycle

2019 Indian FTR 1200 S

My personal translation: Indian is probably working on an adventure bike with this platform. After seeing it in person, it’s very easy to visualize different styling, suspension, tires, ergonomics, etc to morph this platform into a bona fide ADV. It’s a very hot segment and it’s one that Harley-Davidson is about to get into with the Pan America. For Indian, the platform and engine are already done and the brand might even be able to bring an adventure bike to market sooner than the Pan America shows up, which is supposed to be in 2020. Of course, this is just my own speculation, and time will ultimately tell.

From the styling to the pricing to the spec sheet, it sure seems like Indian knocked it out of the park with the FTR 1200. If this thing’s real-life performance is as good as we hope it is, we think Indian Motorcycle will have a global winner on its hands when this bike hits dealers next spring

Indian's marketing director shares with us the secret to the iconic brand's renaissance.

It’s hard to talk about the motorcycle industry in 2017 without talking about Indian Motorcycles. Sales for the Polaris-owned brand have been soaring with double-digit growth while another American cruiser brand which will remain nameless is struggling. Motorcycle sales in the States are down overall but that hasn’t stopped Indian from growing its market share in big bikes from three percent to ten percent in just one year. The boys in Milwaukee still have a comfortable lead in the segment, but the gap is closing faster than anyone could have predicted.

So what’s the secret? What’s the special sauce behind Indian’s success? We reached out to Indian’s marketing director Reid Wilson to find out.

“There are a variety of factors that we believe have played a role in our ability to outperform the industry throughout 2017, no less of which is momentum,” said Reid. “We’ve been able to sustain and build upon the significant momentum we established with key product line introductions in recent years, including Scout and Chieftain, both of which remain consistent performers for us.”

Indeed, the Scout has become a segment leader in entry-level cruisers terms of power, engineering, and style at a competitive price. The Chieftain does everything a touring bike is supposed to do. It’s big on long-distance comfort, modern technology, retro/modern style, and enough special editions to keep it interesting.

“We’ve built on that momentum with a careful balance of commitment to our heritage, coupled with a focus on modern design and performance,” said Reid speaking further to the brand’s momentum. To me, this statement hits the nail on the head for Indian. The brand has found the perfect blend of looking back to its heritage and looking forward to its future. Indian injects just enough “heritage” into its bikes without getting too hung up on it while giving the bikes enough new-school flair and class-leading performance to stay truly modern and competitive. Nobody would mistake a 2017 Indian for a model from 30 years ago, which is something not all American cruiser brands can claim.

That’s a great ethos, so how does it play out in practice? “Examples of this would be successful modifications to some of our popular models, such as injecting the Chieftain platform with a heightened level of attitude through the introduction of the 19-inch wheel and open fender, or the limited edition ‘Elite’ series models for Chieftain and Roadmaster, as well as our popular limited-edition collaborations with Jack Daniel’s,” said Reid. “At the same time, the new Scout Bobber was designed to appeal to a younger consumer that’s seeking a more nimble, aggressive type of cruiser. For that reason, we launched the bike at X-Games in Minneapolis at a huge party we hosted for the top action sports athletes and, overall, the launch has been extremely successful for us.”

Another thing about Indian that’s impossible to ignore is its dominant success in flat track racing having recently won the grand national title. “The investment and commitment we’ve poured into Indian Motorcycle Racing in the American Flat Track series is paying off, reminding riders that our brand remains one grounded in the highest levels of innovation and performance,” said Reid.

We asked Indian what the brand is planning on doing to continue this momentum. “First, and foremost, we will be maintaining our steadfast dedication to the customer, providing a product that consistently delivers in terms of timeless style, unmatched quality, and performance. These characteristics will remain the cornerstone of the Indian brand,” said Reid. “We will also honor the spirit of innovation and exploration that the Indian brand was founded upon more than a century ago, venturing into new categories with new models that push forward and expand Indian’s relevance with a wider range of riders.” To put it simply, Indian figured out a winning formula and it’s sticking to it.

Any brand that’s old enough can hang its hat on “heritage” and “character” and call it a day. But that isn’t cutting it anymore. Indian is proving that it takes more than a “Since 1901” inscription on the engine to sell bikes. The motorcycles have to be truly new and innovative while proving their performance, sometimes by becoming flat track champions. If the competition can’t keep up, it will continue losing relevance until Indian is king again for the first time in about century.

Source: Here’s Why Indian Motorcycles Is Growing While the Competition Struggles

It was 1949 and Indian Motorcycle was struggling. It was so bad that the company could not fulfill the orders it had from, all-important police and other commercial entities. West Coast distributor Hap Alzina got the news and selflessly shipped huge stocks of parts he had in his West Coast warehouse, just so Indian could build bikes to fulfill its orders. Then, not long after that, Alzina learned that Indian was to the point of being so cash strapped, it wasn’t going to be able to meet payroll. Again, Alzina went into action to try to save the manufacturer, by placing a massive advance order, well over his normal allotment, just so Indian would have an instant cash infusion and be able to pay its employees.

Alzina’s ardent devotion to Indian motorcycles went back to the early years of America’s first major motorcycle company. When he was just 15 years old, he bought he first Indian and he loved it. So much so that when he was 17, he took a job as a mechanic for an Indian dealership in San Francisco and quickly worked his way up to service manager.

Born on September 14, 1894, Loris Alzina’s interest in motorcycling began early in life. As a boy he bought his first motorcycle, a Reading-Standard, for $50. In 1909, Alzina’s family moved from Santa Cruz, California, to San Francisco. There, he bought his first Indian from C.C. Hopkins, who was the Indian distributor for Northern California at the time. It was for Hopkins’ agency that Alzina began working for Indian.

Alzina spent 56 years devoting himself to motorcycling. Involved in motorcycling from its infancy, he is best known for being the western states distributor for Indian and, later, BSA. He oversaw the sales of those brands during the height of their popularity. Alzina — who earned the nickname “Hap” from his good-natured attitude — also sponsored many of the top AMA professional racers.

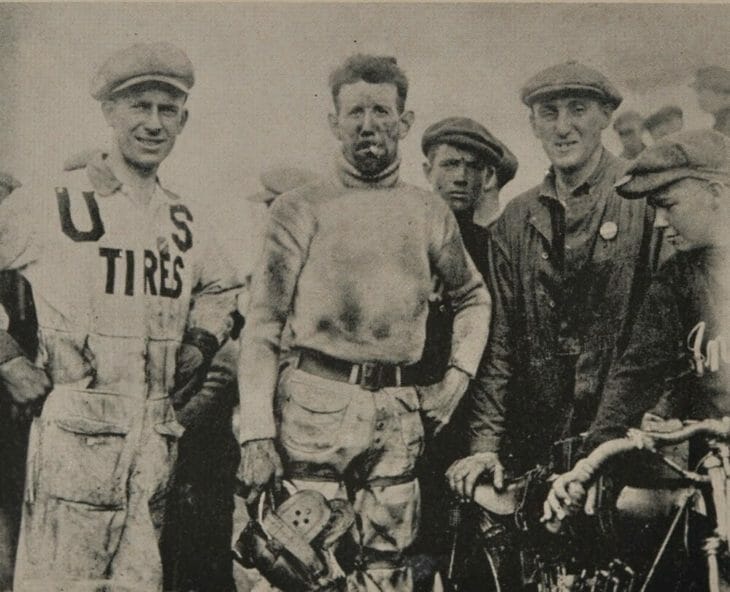

In the early 1910s, racing was becoming increasing popular and Alzina tried his hand in competition. He did some flat-track racing, but his primary interest was endurance runs. Alzina raced in many of the early desert city-to-city runs that were popular at the time. In 1919, Alzina edged well known racers Wells Bennett and Cannonball Baker to win the prestigious San Francisco Motorcycle Club Two-Day Endurance Run. That was a huge upset victory over two very popular racers. Of the 30 starters in the 680-mile endurance event, only seven riders managed to finish. Competitors had to battle against rain, hail, snow and even a landslide during the February contest. One rider slid off a muddy wooden bridge and was injured when he fell into the creek below. Alzina overcame those obstacles to earn a perfect score, riding an Indian sidecar outfit. Bennett, riding an Excelsior and Baker, on a factory-backed Indian, were on solo machines.

Alzina’s 1919 endurance victory was his biggest achievement as a competitor and it made him a popular name by way of win ads in motorcycle magazines across the country.

A few years before his big race win, Alzina opened his own dealership, selling Reading-Standard and Cleveland motorcycles. That enterprise was short-lived due to the onset on World War I. After closing his shop, Alzina again worked as sales manager for San Francisco’s Indian distributor. In 1922, Alzina saw a golden opportunity across the Bay in Oakland and bought out the dealership of E.S. Rose. Alzina turned the struggling franchise into a very successful business.

Alzina’s business expertise was recognized by Indian. In 1925, the company assigned him all of Northern California’s distribution. The next year, he was given the entire state, and by 1927 his territory expanded to include Nevada, Arizona and Washington. By 1948, Indian sales in Alzina’s territory represented over 20 percent of Indian’s total worldwide volume.

At the age of 54, moved on to another business venture and bought the western states distribution rights for BSA motorcycles from Alf “Rich” Child in 1949. The growth in motorcycling over the next 15 years was explosive. Under Alzina’s direction, BSA’s western distribution went from three dealerships to 265 dealers in 20 states. The move to BSA helped keep him in the motorcycle business even after his beloved Indian failed in the mid-1950s.

Alzina was an enthusiastic supporter of racing. Many racing stars such as Ed Kretz, Gene Thiessen, Al Gunter, Dick Mann, Kenny Eggers and Sammy Tanner credited Alzina for being a big part of their success. Several of those riders worked in Alzina’s shop and were allowed generous time away to travel to races.

At one point, Alzina also served as Vice President of the AMA.

Famous for his practical jokes, Alzina once walked a horse through a plush New York hotel lobby, pushing the horse into an elevator and taking him up to a room where a party was going on. He also enjoyed marking “Private & Confidential” on the address side of post cards so that everyone would be sure to read the card.

Alzina retired in 1965. He and his wife, Lillian, enjoyed traveling together, visiting friends across the country during their retirement years. He was given an Award of Merit from the AMA on behalf of its 70,000 members upon his retirement.

He was by a journalist if he viewed motorcycling as more business or pleasure.

“Motorcycles are a business,” he said. “But now, as you’re asking questions and I look back over the years, I call it 40 years of fun.”

Alzina died on July 21, 1970 at the age of 75. He will always be remembered as a man of integrity, honesty, loyalty, foresight, common sense and hard work. He was also a one of Indian’s most passionate supporters. He was inducted into the first class of the Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 1998.

Larry Lawrence | Archives Editor – Cycle World In addition to writing our Archives section on a weekly basis, Lawrence is another who is capable of covering any event we throw his way.

Motorcycle Restoration part of nostalgia trip

BOULDER (AP) — A growing band of once nearly extinct Indians is being resurrected in Boulder, some restored from rusting graveyards while others quietly survived the decades until their time had come again.

Not the red-blooded variety of hostiles these, but iron and steel Indian motorcycles built at the old Wigwam factory in Springfield, Mass., before the firm went bankrupt in 1953, leaving Harley Davidson as America’s lone motorcycle manufacturer.

“Save a piece of America — restore something,” is how machinist and tool-and-die maker Jeff Grigsby explains why he got into his growing business of restoring the old Indians to better-than-new condition.

Grigsby, born the year Indian went broke, says his customers are a “well-to-do crowd” since his inside-out restoration jobs run $7,000 to $9,000 on the Chiefs, the big 74-to-80 cubic inch V-twin Indians.

Back in the 1950s after Indian went broke, a dollar-short generation of young riders bought up those big, graceful but distressed Chiefs for $150 to $300. They hacksawed the full-skirted fenders into bobtails and destroyed them in street-drag duels with the quicker, lighter British bikes then flooding the market.

Only a few Indians survived.

Grigsby says there are more than 20 of the Indians running around the Boulder area now, ranging from well-worn to concourse condition. They include the rare Indian 4-cylinder machines, mostly the big V-twin Chiefs, and even a 1915 Power Plus twin.

One of those Indian riders is Eldon Arnold, 58, who bought his 1950 80-inch Chief 23 years ago and now has about 60,000 miles on it.

“You can’t wear them out. With a little extra care they’ll run forever. As the years went by, the Indian got more valuable and I hated to go out on the road with it. And at one time, parts were hard to come by. But they’re being duplicated again now,” Arnold said, summing up the nearly three decades since Indian went broke.

Ninety percent of American motorcycling today is done on Japanese bikes. Grigsby thinks increasing interest in the old Indian bikes is because they were American-made and represent a vibrant, classic era in motorcycling.

“It’s a study of history, of American engineering,” Grigsby said of the Indian bikes who battled Harley, Excelsior, Henderson, Pope and Cyclone for race track and sales supremacy during the golden age of American motorcycle production.

Indian began production in 1901, won the nation’s first motorcycle race (a 10-miler at Brooklyn, N.Y.) in 1902, then entered international Gran Prix racing and swept Britain’s Isle of Man 1-2-3 in 1911.

Every U.S. national motorcycle championship in 1928 and 1929 was won by an Indian.

“A Harley rider looked on an Indian rider like a racist thing. It was blood for blood back then and Indian still held all the speed records — and that determined the sales of a lot of motorcycles,” Grigsby said.

“The Indian is a rarer breed (than Harleys a desirable unit. People that rode these bikes when they were young now realize they can get one in better than new condition.

“I guess it’s a compensation to give up a gas-eatin’ hog for a piece of classic transportation that gets 60 to 65 miles to the gallon on regular,” Grigsby added.

At 27, Grigsby is an 11-year veteran of motorcycle mechanics. He dropped out of school at age 16 to attend a Harley Davidson factory mechanics school and then took a job at a Los Angeles Harley shop.

He took his four-year machinist’s apprenticeship in Boulder with Ed Gitlin at the shop where Grigsby still does his machining trade.Grigsby had balanced, tuned and blue-printed Harley V-twins for several years before “I fell into a large investment of close to 40 Indian motorcycles three years ago.”

Since then he has restored five of the Indians, with three more underway for completion in March. He hopes to expand to 12 at a time for the next batch. “Everybody that sees ‘em, wants ‘em.”

Partner in the effort is Jim Arnold, Eldon’s son, who restores the Indians’

instruments, speedometers, switches and does all detail work.

Grigsby says his Indians go through five stages of complete dismantling and reassembly. The final finish and fit is more like that of a hand-built Italian Ferrari than the original, production Springfield Indians.

Grigsby replaces plain bronze bushings with needle bearings wherever possible, Teflon-coats engine parts, mirror polishes combustion chambers and improves on the original lubrication system.

If the Indian was such a classic, why did the firm go belly up?

Cycling historians say loss of World War II government contracts when the military opted for the Jeep instead of courier motorcycles and a fatally flawed new British-style engine marketed after the war — it consistently blew main bearings — led to Indian’s defeat.

Now, 27 years later, restorers like Grigsby and Arnold at shops scattered across the country are bringing the last remnants of the old Indian line back to showroom condition as America’s nostalgia kick moves into the motorcycling arena.

And after so many moons, the end of the trail for Indian has become a new beginning.

Editors Note:This reprint is from 1980. Jeff is still active with building musem quality Indian Motorcycles. He is one of many rebuilders who have kept the brand alive!