Ted Williams was out in his red barn of a work shop the other day talking motorcycles ‑ real motorcycles, Indian Motocycle motorcycles..

“Some of these things they’re coming out with today don’t even like a motorcycle at all. One looks just like a chemical toilet to me” he said. “A chrome plated Porta‑Potti.”

That is unlike the Indian, a proud American nameplate that hasn’t been manufactured for a generation but is still beloved and remains Williams’ standard by which any motorcycle is judged —— and to which none measures up.

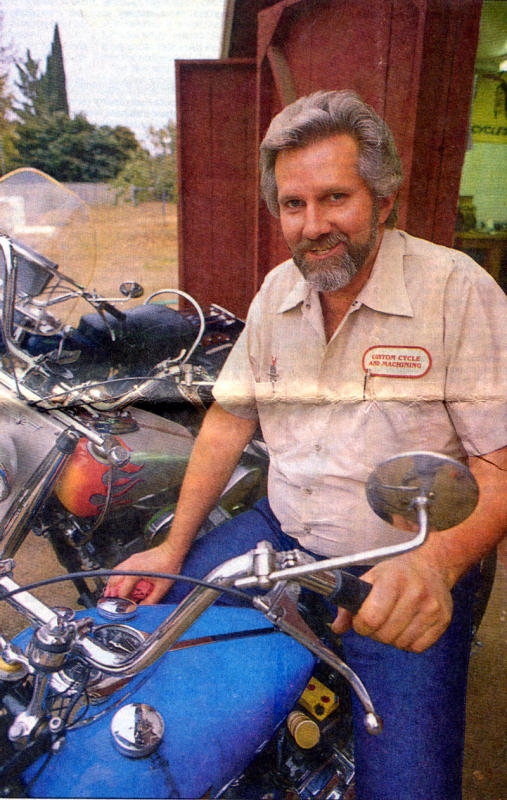

Williams, 44, big, brawny and intense, his sandy brown hair carefully styled, his fingers as clean and manicured as a banker’s, holds forth in a surgically tidy shop behind his house on the edge of town here, earning his living looking after the health of Indian Motocycles.

“If you’ve got all day and you won’t get bored, sit down and I’ll tell you what it is about the Indian,” Williams said with a smile as he took a breather from modernizing the rear brake on a customer’s 40‑year‑old Indian Chief, the most popular and successful of the Indian models.

In essence, he said, it is the machine’s brute strength, the manly vibration of the giant V‑twin engine, the down‑home simplicity of the engineering, that make the Indian superior, in his opinion, to other makes of motorcycles.

“All the nuts and bolts are just stock items. You can go into any good auto‑parts store and buy spark plugs and other ignition parts. The only thing that’s getting a little hard to find now is tires, but you can still get them if you know where,” he said.

He then told a brief history of the nameplate. The Indian Motocycle (no R) burst onto the scene in 1901, manufactured by George Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom in Springfield, Mass.

It earned a place beside Harley Davidson as a leading American brand, going strong through World War II. But. after the war, management lost interest in the big, brute force v-twins and began bringing out new models that were beset by bugs.

English interests acquired control during the crisis, and the last 80‑cubic‑inch, deep‑throated, man‑sized Indian Chiefs were built in 1953. (That is, except that 50 were assembled from parts collected from the dusty shelves of the Springfield factory in 1955 to fulfill a contract with the New York Police Department, and five civilian Chiefs that were turned out in the same batch.)

The English owners tried for a few years to palm off various English machines by plastering them with Indian decals, but American Indian buyers weren’t fooled for an instant by such blatant forgery. The company passed into history, but the good, will among the American motorcycle community lived on and is growing.

Williams estimated that 40,000 Indians remain on the road today out of, the hundreds of thousands that wire manufactured. “But that’s more than there were 10 years ago, and there were more then than there were 20 years ago.”

People keep finding old machines and bringing them back to life, which is where Williams comes in.

He said he grew up working on Indians in his father’s Orange County garage, and after a hitch in the Navy and spells of trying such work as air conditioning repair, he ended up working in a motorcycle shop that catered to the faithful numbers of Indian owners.

Then, four years ago, he and his wife, Maureen., decided to move to rural Sutter County out of Orange County’s smog and crowding. The word got out among owners of Indians, and his trade followed him.

Owners are willing to seek him out for his skill in ministering to the fine old machines, including modifications that cure several fatal flaws in the original design and other changes that increase the engine size up to 95 cubic inches and more to make the old Chiefs dazzling performers.

Williams himself owns three Indians in roadworthy shape, a soupedup Scout of indeterminate age and a pair of 1953 Chiefs, one with a 95‑cubic‑inch engine.

“I had a Harley‑Davidson once,” he said with a note of distaste for the name of the rival make. “I bought it as a basket of parts for $5, put it together, and sold it for $50. 1 didn’t want it. I’m an Indian man.”

Editors Note: Ted Williams is still working on Indians and can be reached at: unkown