New Beginning at end of Indian Bike Trail

Motorcycle Restoration part of nostalgia trip

BOULDER (AP) — A growing band of once nearly extinct Indians is being resurrected in Boulder, some restored from rusting graveyards while others quietly survived the decades until their time had come again.

Not the red-blooded variety of hostiles these, but iron and steel Indian motorcycles built at the old Wigwam factory in Springfield, Mass., before the firm went bankrupt in 1953, leaving Harley Davidson as America’s lone motorcycle manufacturer.

“Save a piece of America — restore something,” is how machinist and tool-and-die maker Jeff Grigsby explains why he got into his growing business of restoring the old Indians to better-than-new condition.

Grigsby, born the year Indian went broke, says his customers are a “well-to-do crowd” since his inside-out restoration jobs run $7,000 to $9,000 on the Chiefs, the big 74-to-80 cubic inch V-twin Indians.

Back in the 1950s after Indian went broke, a dollar-short generation of young riders bought up those big, graceful but distressed Chiefs for $150 to $300. They hacksawed the full-skirted fenders into bobtails and destroyed them in street-drag duels with the quicker, lighter British bikes then flooding the market.

Only a few Indians survived.

Grigsby says there are more than 20 of the Indians running around the Boulder area now, ranging from well-worn to concourse condition. They include the rare Indian 4-cylinder machines, mostly the big V-twin Chiefs, and even a 1915 Power Plus twin.

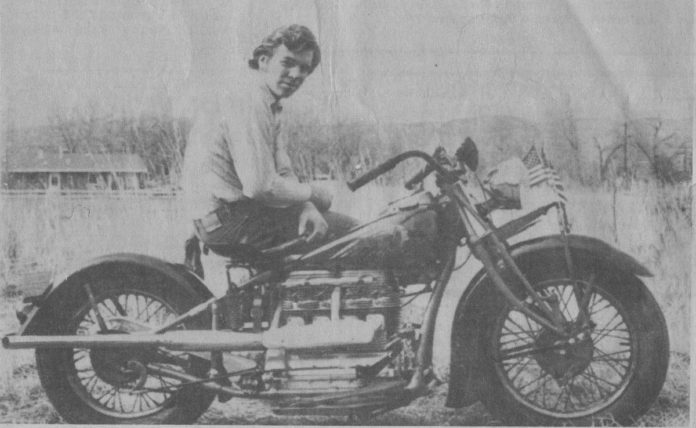

One of those Indian riders is Eldon Arnold, 58, who bought his 1950 80-inch Chief 23 years ago and now has about 60,000 miles on it.

“You can’t wear them out. With a little extra care they’ll run forever. As the years went by, the Indian got more valuable and I hated to go out on the road with it. And at one time, parts were hard to come by. But they’re being duplicated again now,” Arnold said, summing up the nearly three decades since Indian went broke.

Ninety percent of American motorcycling today is done on Japanese bikes. Grigsby thinks increasing interest in the old Indian bikes is because they were American-made and represent a vibrant, classic era in motorcycling.

“It’s a study of history, of American engineering,” Grigsby said of the Indian bikes who battled Harley, Excelsior, Henderson, Pope and Cyclone for race track and sales supremacy during the golden age of American motorcycle production.

Indian began production in 1901, won the nation’s first motorcycle race (a 10-miler at Brooklyn, N.Y.) in 1902, then entered international Gran Prix racing and swept Britain’s Isle of Man 1-2-3 in 1911.

Every U.S. national motorcycle championship in 1928 and 1929 was won by an Indian.

“A Harley rider looked on an Indian rider like a racist thing. It was blood for blood back then and Indian still held all the speed records — and that determined the sales of a lot of motorcycles,” Grigsby said.

“The Indian is a rarer breed (than Harleys a desirable unit. People that rode these bikes when they were young now realize they can get one in better than new condition.

“I guess it’s a compensation to give up a gas-eatin’ hog for a piece of classic transportation that gets 60 to 65 miles to the gallon on regular,” Grigsby added.

At 27, Grigsby is an 11-year veteran of motorcycle mechanics. He dropped out of school at age 16 to attend a Harley Davidson factory mechanics school and then took a job at a Los Angeles Harley shop.

He took his four-year machinist’s apprenticeship in Boulder with Ed Gitlin at the shop where Grigsby still does his machining trade.Grigsby had balanced, tuned and blue-printed Harley V-twins for several years before “I fell into a large investment of close to 40 Indian motorcycles three years ago.”

Since then he has restored five of the Indians, with three more underway for completion in March. He hopes to expand to 12 at a time for the next batch. “Everybody that sees ‘em, wants ‘em.”

Partner in the effort is Jim Arnold, Eldon’s son, who restores the Indians’

instruments, speedometers, switches and does all detail work.

Grigsby says his Indians go through five stages of complete dismantling and reassembly. The final finish and fit is more like that of a hand-built Italian Ferrari than the original, production Springfield Indians.

Grigsby replaces plain bronze bushings with needle bearings wherever possible, Teflon-coats engine parts, mirror polishes combustion chambers and improves on the original lubrication system.

If the Indian was such a classic, why did the firm go belly up?

Cycling historians say loss of World War II government contracts when the military opted for the Jeep instead of courier motorcycles and a fatally flawed new British-style engine marketed after the war — it consistently blew main bearings — led to Indian’s defeat.

Now, 27 years later, restorers like Grigsby and Arnold at shops scattered across the country are bringing the last remnants of the old Indian line back to showroom condition as America’s nostalgia kick moves into the motorcycling arena.

And after so many moons, the end of the trail for Indian has become a new beginning.

Editors Note:This reprint is from 1980. Jeff is still active with building musem quality Indian Motorcycles. He is one of many rebuilders who have kept the brand alive!